Return to Sitka.com – Return to Sitka Stories and News

Collected from the United States Senate Stories

April 8, 1867

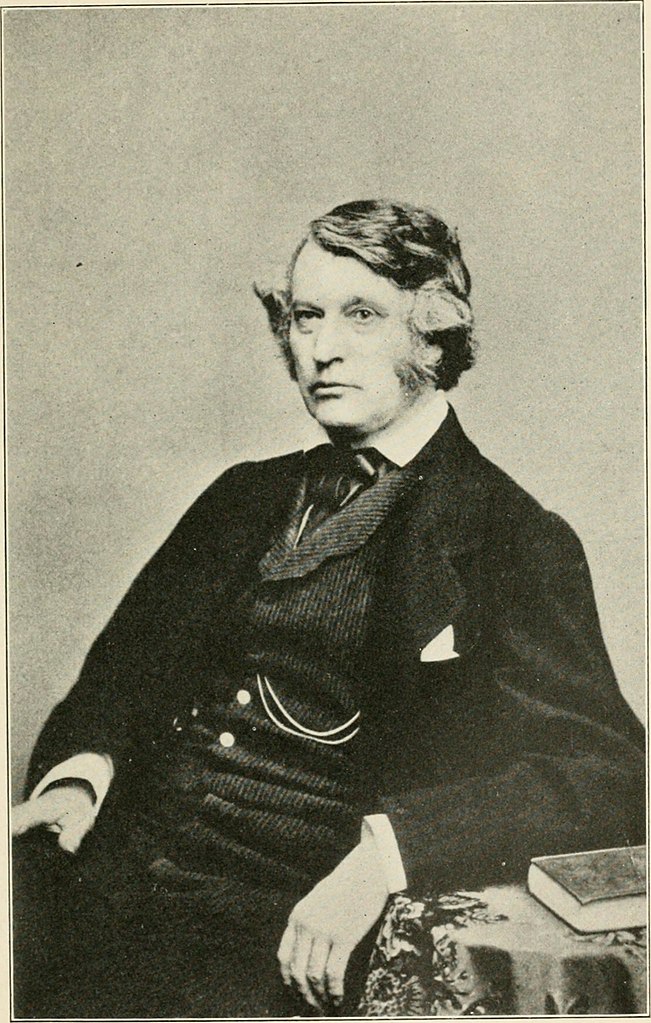

It’s been called “Seward’s Folly,” but it could just as well be known as “Sumner’s Project.” As history books tell the story, in 1867 Secretary of State William Seward secretly negotiated with Russian officials to purchase the Alaskan territory for $7.2 million, putting Alaska on the road toward statehood in 1959. That is just part of the story. That treaty had to be approved by the Senate. To clear that hurdle, the secretary of state needed the support of the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, Charles Sumner.

The Senate, along with most of the American population, was very skeptical about the wisdom of Seward’s purchase. It was mocked as Seward’s Folly, Seward’s Icebox, and Seward’s Polar Bear Garden. What do we want with a territory covered with “glaciers, icebergs, bears and walruses?” asked one critic. “Russia has sold us a sucked orange!” proclaimed the New York World. Why should we invest in this “territory of ice, snow and rock,” queried newspaper editor Horace Greeley. Surely, he insisted, the money “would be better spent reducing the income tax.” Senator William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, a fervent critic of Seward, joked that he’d vote for the treaty only if it stipulated “that the Secretary of State be compelled to live” in Alaska.

At first, Sumner also was skeptical. He was an expansionist and had favored a greater U.S. presence in North America, but like his colleagues he knew very little about this faraway land. He worried that this acquisition might lead to other “indiscriminate and costly” annexations. Consequently, when Seward presented the treaty for approval, Sumner maneuvered the agreement into his committee for investigation. That move perhaps saved the Alaska Purchase Treaty.

A scholar by nature, Sumner immersed himself in an intense study of the Russian-held territory. Calling on the resources of the Library of Congress and the new Smithsonian Institute, he spent countless hours buried in maps, journals, pamphlets, periodicals, atlases, newspapers, manuscripts, and more than 100 books—written in English, German, French, and Russian—only the latter presenting a challenge to this natural linguist. “I am living with seals, and walruses, and black foxes,” he confided to a friend. As one historian has written, what Sumner learned about Alaska transformed him from “a skeptic into a powerful persuader.”

On April 8, 1867, Sumner addressed the Senate. With a single sheet of notes to guide him, explained a biographer, he spoke for three hours in support of the treaty, presenting a virtual “encyclopedia of all the facts then known” about Alaska. He concluded “with a brilliant summary of scientific data on the topics of population, climate, productions of soil, mineral products, and fisheries.” As a final thought, Sumner added that the newly acquired land must not bear “any name borrowed from classical antiquity,” but instead its name must be “indigenous”—namely, Alaska. The next day, the once-skeptical Senate approved the treaty for ratification by a vote of 37 to 2.

A week later, Sumner penned a note to his good friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “I have been tried a good deal by the Russian Treaty,” he wrote, but it “has given us a new world with white foxes & walruses not to be numbered.” If it hadn’t become “Sumner’s Project,” the Alaska Purchase Treaty might have remained just “Seward’s Folly.”