Return to Sitka.com – Return to Sitka Stories and News

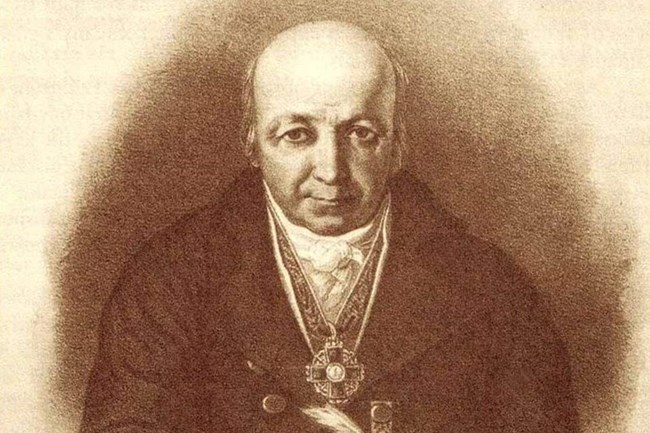

Baranov Establishes Settlement on Sitka Sound, 1799

Excerpt from Alaska – Its History, Climate, and Natural Resources by Governor A.P. Swineford – Published 1898

In April, 1799, Baranov sailed from St. Paul with two vessels, one of which had been built at Prince William Sound during the preceding winter, and a fleet of 200 canoes, with a view of establishing a settlement on Norfolk (now Sitka) Sound. Thirty of his canoes were swamped in a heavy sea off Cape Suckling, by which he suffered a loss of sixty men. Soon after, his fleet of canoes having landed for the night, those on shore were attacked by natives, in the dark, and here again he lost about thirty men and a number of canoes.

On the 25th of May he landed at what is now known as Old Sitka, near which point he found the English ship Caroline at anchor. He found the natives hostile and inclined to resist his attempt at settlement, but succeeded in capturing a number of hostages, and having effected an agreement with Kattlaan, the then ruling chief of the Sitkas, proceeded at once with the building of a fortified post.

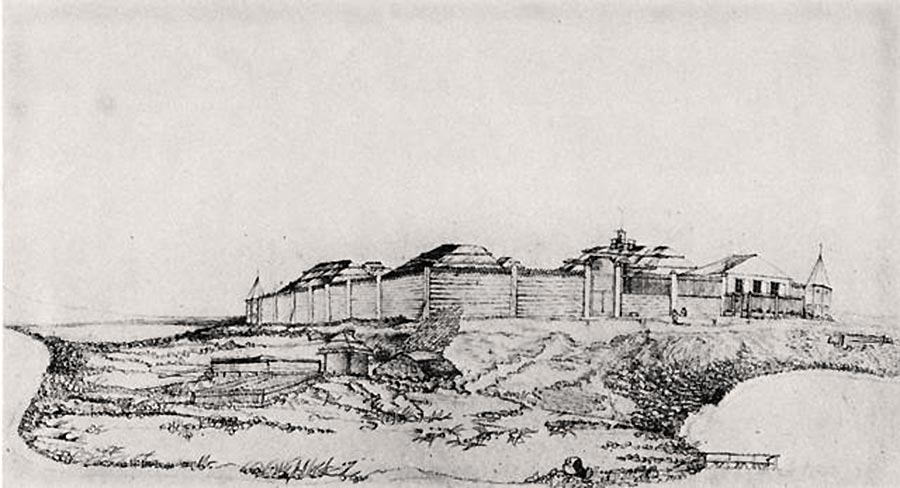

The fort consisted of a stockade, with blockhouses over cellars, two stories high, on each corner. The other buildings were one large two-story structure, with basement and veranda on all sides, a large house occupied by the Aleutian hunters, a blacksmith shop, cook house for laboring men, bath house, warehouse, and a small building on the summit of a hill, somewhat resembling that on which the castle was afterwards located in Sitka, but which was called the “ke-koor.” The latter was occupied by the Governor, and history asserts, was the most illy constructed of the lot, Baranov having more regard for the health and well being of his men than for his own ease and comfort.

Before the party moved into the fort they lived in tents, and the exposure was such that several diseases became prevalent among them, principal of which was scurvy. The force consisted of twenty-three Russians and fifty-five natives from the Aleutian Islands, and during the months of November and December preceding the completion of the fort they experienced great hardships, being obliged to subsist principally on the flesh of the walrus and hair seal.

In April, 1800, Baranov left the fort, which he had named Archangel, in charge of a Mr. Medvednakoff and returned to Kadiak, having, as he thought, firmly established his settlement and secured the friendship and good will of the adjacent natives. He then proceeded to establish settlements in Prince William Sound, at the mouth of Kaknu River, Ilyamna Lake and other points, some of which were immediately afterwards destroyed by the natives.

In July, 1802, the fort and settlement known as Old Sitka, to which Baranov had given the name of Archangel, was attacked and destroyed by the Thlinkets, who killed nearly all the settlers. At that time there was a native village at the mouth of the Indian River and another and larger one on Crabapple Island, in Sitka Sound. The natives of these two settlements were joined by many others from a distance in a well-planned surprise of the small garrison, and the attack was so sudden and unexpected that practically no defense was made, the vessel which had been left by Baranov for the protection of the place being absent at the time. A letter written by Ambrosium Plotnikoff, one of the garrison, which was found in the counting-house of the Russian- American Company after the transfer of Alaska to the United States, gives the following account of the massacre:

“In 1802, on the 27th day of July, about half-past 1 o’clock in the afternoon, I went to the creek to look after the cattle, for which duty I had been detailed by William Medvednakoff, our Superintendent. Shortly after my return I saw a large number of Tlingits gathering around the house occupied by the working people. The Indian chief, Michael, was talking very loud and excitedly addressing his people, but, not being acquainted with their language, I could not understand what he was saying. Shortly afterward I saw over sixty canoes coming around the Point, and I immediately started for the house. To my surprise, I found all the doors fastened on the inside, so I started back and ran into the stable, where I had always been in the habit of keeping a gun. I found there the wife and child of one of the employees, who at my suggestion sought refuge in the woods. As soon as she left I barricaded the doors and windows and loaded my gun.

Soon after four Indians came to the door, demanded admission, and, forcibly gaining entrance, overpowered me, but I shortly after liberated myself and ran into the woods, leaving my coat and gun in their hands. After awhile, being very anxious to know the outcome, I returned to a point near the fort and found all the buildings on fire except the warehouse, of which the Indians had possession, and from which they were throwing the furs, provisions, etc., out through the windows and carrying them to the canoes which had been brought for the purpose of taking them away. I saw one of our men jump through a window of one of the burning buildings, only to be picked up on the fighting knives of the savages and thrown back into the fire. I also saw them cut off another man’s head and throw the headless body into the flames.

While I was standing there looking on I noticed two Indians running toward me, and at once took shelter behind a big tree, under cover of which I again ran into the woods. In the evening I again returned to take a look at the mournful scene. The buildings were still burning, and I noticed a little ways off some of our cattle with knives sticking in their backs and sides and endeavored to relieve them, but was discovered by the natives, and had to retreat again into the woods, where I remained during the night. Early next morning I heard the discharge of muskets, and, being frightened, I started for the mountain, and on the way met a woman and her child and a sick man, who had escaped.

We all continued on to the mountain, returning to the vicinity of the fort nearly every night to lament over our departed brethren. In this way, without food, we passed eight days. On the eighth day, about noon, I heard two reports of a cannon, and, requesting my companions to remain quiet until my return, I went to learn the meaning of the reports. As soon as I got out of the woods I saw a ship which I at first thought was our war vessel, the Katherina, but which on nearer approach proved to be English. When she came within hailing distance I endeavored to make myself heard and seen, but could not succeed in attracting the attention of those on board. I was, however, noticed by some Indians in the vicinity, and felt compelled to retreat once more into the woods, where I remained until dark, when I again went down to the beach, taking a route which brought me nearer to the ship.

I hailed her successfully this time, and a boat was sent for me and I was taken on board. I informed the Captain of what had taken place and then returned to my companions and found that another man, named Batoorin, had joined them during my absence. We then all returned to the beach and were taken on board ship. Batoorin and I asked the Captain to send a boat to the fort, which request was granted, and a boat with an armed force in command of the Captain himself was dispatched to the shore, taking me along.

The Captain and myself were the first to land, and we soon discovered several of my dead brethren, whose heads had been completely severed from their bodies, and whom we afterwards buried. Among the ruins we found pieces of copper, but nothing else. The vessel remained three days in the harbor, and on the third a canoe came alongside, with Michael, the chief of the Sitka tribe. He inquired at once if there were any Russians on board, which inquiry convinced the Captain that they were not aware of our rescue and he replied that he had not seen any Russians since his arrival. At the same time he requested us to go below and remain, and then by kind and reassuring words he induced Michael, his nephew, and a squaw to come on board.

I at once recognized the squaw as the former servant of one of our men, and jumped to the conclusion at once that she had all along been playing the spy and informer. Getting them on board, the Captain ordered that they should be doubly ironed, after which he informed them of our presence and told them that they would not be liberated until they had returned all the stolen furs, etc., and brought on board all the men, women and children of the settlement who had not been killed, but reserved for a life of slavery. He assured him also that in case his order was not strictly complied with he would certainly hang him (Michael) to the yardarm.

While this talk was going on two more English vessels came to anchor close by, the Captains of which came on board our ship, when I immediately recognized one of them, whose name was Abbot, and who had frequently visited Archangel. A consultation was had between the three Captains, the result of which was an order that the captured persons and property be brought on board without further parley or delay, and the Indians, anxious for the life of their chief, lost no time in bringing in two women and four children, asserting that they had no more. After the arrival of the two ships referred to, it should have been remarked, canoes came out to the ship in large numbers.

Having ascertained from those who were returned that quite a large number of others were still detained by the Indians, and they positively refusing to surrender any more, the Captain ordered his crew to fire on the canoes and their occupants. After a large number had been killed they begged for mercy, and promised to comply with the order to bring in the prisoners, when the firing ceased, and the remainder of the women and children were brought to the ship. From the last comers I ascertained that they still held one man, named Taradonoff, prisoner, and I informed the Captain of the fact.

The Indians then begged the Captain to liberate their chief, which he declined to do, informing them that they still held one Russian a prisoner, and that he too must be delivered up. Then they went off and brought Taradonoff on board, together with a large quantity of furs, when the chief and his two companions were released, though we begged the Captain to take them to Kadiak. After securing supplies from the other ships the one which had rendered us such opportune aid sailed for Kadiak, where we all arrived after a five days’ voyage, more than thankful to the English Captain who had saved our lives.”

Written by Ambrosium Plotnikoff, Russian American Company employee at Old Sitka in 1802

Addendum:

Old Sitka National Historic Landmark commemorates the first European settlement in the Alexander Archipelago and an incident in Russian-Native relations. In 1799, in order to check international trade competition, Alexander Baranov, Chief Manager of the Russian American Company, met with local Tlingit Chiefs to obtain cession of the site for a new post. Only a barabara was on the Starrigavin River site when the Russians constructed Redoubt St. Archangel Michael. It consisted of several log buildings surrounded by a fort wall when, in June of 1802, a Tlingit attack destroyed the Redoubt. The Russians reestablished at Sitka and the original site became known as Old Sitka. In 1934-1935 archeologists excavated a portion of the site, determined the locations of some Russian buildings and recovered many artifacts. Erosion and extensive construction activity has destroyed much of the area excavated. In 1966, the State built a wayside on the site. It is now operated as a unit of the Alaska State Park System open for year-round use.